T.S. Elliot, The Dry Salvages, Nº3 of Four Quartets

I do not know much about gods; but I think that the river

Is a strong brown god—sullen, untamed and intractable,

Patient to some degree, at first recognised as a frontier;

Useful, untrustworthy, as a conveyor of commerce;

Then only a problem confronting the builder of bridges.

The problem once solved, the brown god is almost forgotten

By the dwellers in cities—ever, however, implacable.

Keeping his seasons and rages, destroyer, reminder

Of what men choose to forget. Unhonoured, unpropitiated

By worshippers of the machine, but waiting, watching and waiting.

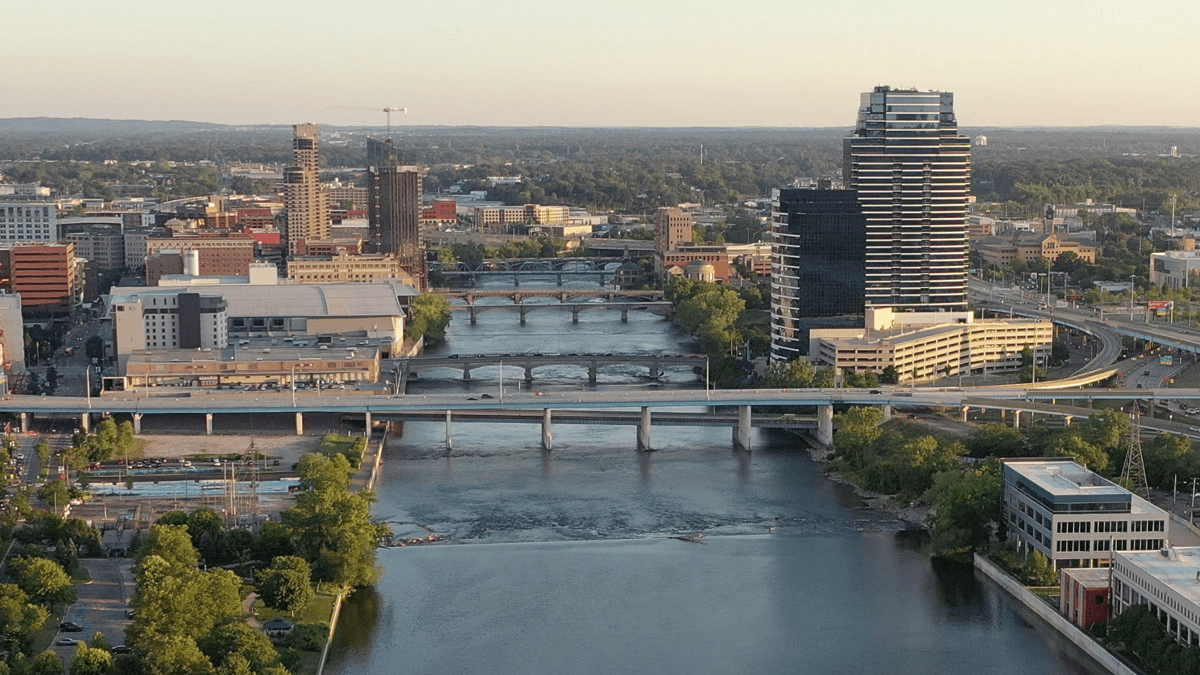

The beginning of T.S. Elliot’s poem “The Dry Salvages” which he takes from a boyhood memory of a spot he once enjoyed, could well have been written to describe the Grand River. The Grand is strong and intractable. It once was a wild and bountiful fishing ground for the Ottawa Indian tribe. Through furs, logs and other industry, the river was a conveyor of commerce but, once that work was done, it became largely forgotten as the City grew around it.

With this revitalization project, the Grand River will be forgotten no more. We honor its history by recapturing fish habitat and the spirit of the rapids that once prompted Captain Charles E. Belknap to recall, “…made a noise that broke the stillness of the forest and echoed from the neighboring hills.”

At the same time, we look to the future of a river that is safe and accessible to kids who want to learn how to fish, boat or swim. A river that is a great fishery for salmon and steelhead but also for walleye, bass and many other species. A river that attracts people to its waves, shores and to the City for which it is the centerpiece. We mean to respect the history of the river by recapturing the spirit of the rapids, while at the same time becoming a catalyst for Grand Rapids’ continued success long into the future. Never have I been involved with a project that required such clear perception of the past and vision of the future.

We mean to respect the history of the river by recapturing the spirit of the rapids, while at the same time becoming a catalyst for Grand Rapids’ continued success.

There is an excellent summary of the River’s history in pictures and drawings in an article originally posted in 2017 and updated in 2019 from then-MLive writer Amy Barczy (Biolchini).

The article includes a drawing in which the rapids are depicted in the heart of downtown. The caption notes that, “This portion of a hand-drawn map circa 1830 depicts the rapids in the Grand River. In this map, north is on the right. The small island in the river is the approximate location of the JW Marriott Hotel in downtown Grand Rapids.”

Figure 1: This map from 1830 shows the Grand River coming through downtown Grand Rapids. Today, the JW Marriot stands (approximately) in the location of the small island in the river.

[IMAGE CREDIT: Grand Rapids History & Special Collections, Archives, Grand Rapids Public Library, Grand Rapids, MI]

Ms. Barczy’s article also provides these references:

- “These rapids are about a mile in extent and 300 yards wide and must have at least a 10-foot fall, some think 15,” said an 1826 article about the river that appeared in the National Intelligencer. “They are crowded with huge round rocks, among which the water roars and foams with great fury.”

- The rapids still made their presence known in 1838, when a visitor, Frank Little, wrote that the “incessant, impressive roar of the rapids” kept him up at night as he slept.

There is now a city in the way so we cannot duplicate the actual historic rapids. There simply is not enough of a record of the natural state of the river prior to European settlement to know with confidence where every rock lodged. Nor would that be the only factor in this project. Considerations of safety, flooding, prevention of invasive species and betterment of fish and wildlife habitat are all important matters that strongly influence the design. We are confident that the design we are proposing recaptures the spirit of the rapids while meeting the other goals of the project.

The rapids in the Grand River can never be exactly restored. But the spirit of it can be revitalized.

As discussed in a previous blog the Grand Rapids WhiteWater project is effectively divided in two: the Lower Stretch, which is roughly from Bridge Street to Fulton Street, and the Upper Stretch, which is planned from the North end of the Lower Stretch to the proposed Adjustable Hydraulic System between Leonard and Ann Street. Since the federal government is determining the placement and design of (and paying for) the sea lamprey barrier that anchors the Upper Stretch, we will not complete the design for the additional in-river features in the Upper Stretch until we have better direction from the federal government.

Shortly, however, we will submit the proposed design and associated permitting documents for the Lower Stretch to the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes and Energy as part of our permit application. The proposed design, depicted below, is the culmination of over ten years of scientific study and research and has been developed in close coordination with multiple state and federal agencies.

Figure 2: Image depicts proposed substrate sizes with red representing large boulders and smaller sizes of rock and alluvium depicted in the other colors.

Figure 2: Image depicts proposed substrate sizes with red representing large boulders and smaller sizes of rock and alluvium depicted in the other colors.

The design of the Lower Stretch removes four dangerous low-head dams and includes four channel-spanning hydraulic features designed to increase flow diversity, improve aquatic habitat and aesthetics, and create and enhance recreation opportunities in the Grand River. Specifically, four wave features, two in front of Ah-Nab-Awen Park , one in front of the Grand Rapids Public Museum and one in front of the L.V. Eberhard Center of Grand Valley State University have been incorporated into this design to provide whitewater recreation opportunities.

- The Lower Stretch is about 400-500 feet wide and the wave features represent approximately 60-70 feet of the channel width. This is important as most of the river will not be punctuated only by rapids for whitewater recreation, but by large riffles (riffles are the shallower sections of a stream where rocks break the water surface and are very important to fish habitat) and areas of quieter water.

- The intensity of the rapids is indicated by color in the image below (the red being the most intense, the blue the least), and the speed of the water decreases as the river flattens out from North to South. (Because of the natural gradation, the most intense rapids will be in the Upper Stretch just below the present location of the 6th Street dam.)

Figure 3. Computerized hydraulic modeling software was used to predict the speed, depth, and direction of flow for the proposed design. Red shows areas of faster water and blues and greens show areas of slower water.

- The riffles are on the east side of the river, primarily to aid in fish passage but also to enhance user safety. There will be ample room in the river for both fish and people to avoid the more intense water if they should choose to do so. An advantage of this design is that we were able to address specific agency concerns for fish passage by incorporating areas of slower moving water along the edges of the river and around the wave features. We believe this design significantly improves fish passage opportunities compared to the low-head dams currently in the river.

- Another significant advantage of this design is the ability to provide safety for users. Behind every wave, there is a small eddy and pool of water to allow users a chance to collect themselves. There is also easy access to shore shortly after each of the wave features. RiverRestoration.org, our hydraulic engineers, are able to design the augmented wave features to provide for maximum safety while also creating a much more diverse river bottom that benefits fish and other aquatic species.

Figure 4. Renderings of the first and fourth waves that approximate the level of intensity for each of the areas noted in the design. Note that the waves on the Grand River will not cover the entire river width. These examples, from other projects outside of West Michigan, have waves that cover the river’s entire expanse.

While he may not be a poet of T.S. Elliot’s stature, Captain Charles E. Belknap described his boyhood memories of the Grand Rapids.

… My first view was in June 1854, when from the top deck of the river steamer we came up the east channel to land at the Eagle hotel dock. A few days later I was getting acquainted with the town and near the Butterworth foundry met Harry Eaton and his gang, who by way of initiation to the west, proceeded to push me off a slab pile into the river to see if I could swim. I could and struck out for the head of Island No. 1.

… Sitting on a rock in the sun to dry my clothing, I studied the rapids and hundreds of large boulders of granite and lime rock about which the waters rushed.

… In after years I often thanked Harry Eaton for pushing me off that slab pile because it gave me my first day under those wonderful water maples. I was somewhat older before I really appreciated the great sycamores at the water’s edge, the island plateau of giant water elms, the almost tropical mass of grape vine that festooned the trees, and in every depression the wild plum and crab apple that crowded the elder bushes and sumac, and that I came to love the tinkle of bells, on cows that had waded the river to feed on the abundant grass, blended with the music of blackbirds and bob-o-links swaying about the cattails.

— Capt. Charles E. Belknap, The Yesterdays of Grand Rapids, GR Press Sept 9, 1922

When we complete this project, kids will again be able to “study the rapids and hundreds of large boulders of granite and lime rock about which the waters rushed,” enjoy the trees and the music of birds swaying about the cattails.